ST MARY THE VIRGIN. A splendid exterior thanks chiefly to the Early Tudor brick clerestory with its stepped battlements on a trefoiled corbel frieze and its brick pinnacles. The chancel is a little lower and has an odd and rather daring large C19 dormer window with a straight brick gable. W tower and aisles C14, the tower with angle buttresses only at the foot, battlements and a tall leaded spire, the aisles with Dec windows (mostly renewed). S doorway also C14, see the keeled columns and keeled roll-moulding. Battlements were added in brick at the time when the clerestory was built. Addition also of the S and N chancel chapels with brick responds. The aisle arcades are of three bays and give evidence of an earlier church. They are E.E. The N arcade came first: one circular pier, the others octagonal. W respond on a head-corbel. Arches only slightly double-chamfered. The S arcade has all circular piers and normal double-chamfered arches. - PULPIT. The best early C17 pulpit in the county. Dated 1639, but in style entirely Jacobean, complete with a big tester on a long narrow back panel up the wall. The motif of the panels of the pulpit itself is little aedicules on columns. In the centres false perspectives. Strapwork along the sides of the back panels and on top of the tester. - PLATE. Flagon of 1627; Almsdish of 1675. - MONUMENTS. Brass of Jane Lewkenor d. 1614 (the figure nearly 3 ft long). - Monument to the Gwyn sisters, erected 1753. By Sir Henry Cheere. Big, with the usual grey obelisk, a cherub in front of it, leaning on a draped oval medallion with the portraits of the two sisters. Rocaille and foliage at the foot.

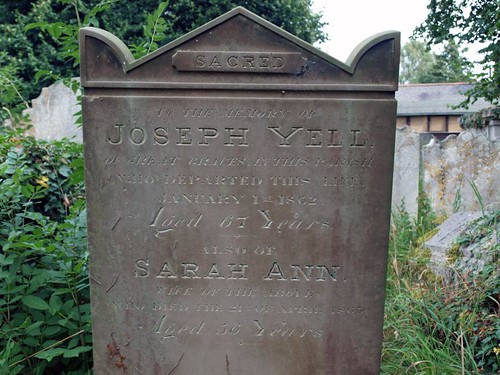

GREAT BADDOW. Here men have lived for thousands of years; their Stone Age and Bronze Age hoards have been found. Its old houses crowd together in winding streets, some backing into the raised churchyard. This churchyard comes into our history, for when the church was new it was a gathering-place of the peasants in their ill-fated rising of 1381.

The most striking feature of the church is the 16th century brickwork of the aisle, and the clerestory springing into view behind. The aisle has a neat crow-stepped parapet, and above the five windows lighting the nave is a corbel table running under the parapet, above which are six cone-shaped pinnacles. A leaded spire rises from the tower, a bell under a little roof of its own jutting out from it.

The oldest things the village has are a few Roman tiles in these walls; they must have been handled by Saxons in a building long since gone. The two arcades and the wide chancel arch give distinction to the church, and there is a touch of humour bequeathed to us by the carver of a bridled head from which one of the arcades springs, a warning against slander. The pride of the church is the Jacobean pulpit. Its elaborate canopy has pinnacles and pendants, and the pulpit has carvings of many beautiful devices. On the chancel wall is a brass portrait of Jane Paschall, who was laid to rest here a few years before they set up the pulpit. She is a fine figure in Elizabethan dress. Two more ladies share the only other striking monument, Amy and Margaret Gwyn, sisters who died in the middle of the 18th century, their portraits being on a marble oval below a cherub.

Here the scholar poet Alexander Barclay came in 1546 as rector. In 1508 he translated Brant’s Ship of Fools into English verse, and then became a monk of Ely, where he translated a life of St George. Scholars owe a special debt of gratitude to Great Baddow, for here also was born Richard de Baddow, who in 1326 founded the Hall which became famous as Clare College at Cambridge.

Simon K -

I got the train to Chelmsford, arriving soon after 8am. I quite like Chelmsford, a thing it is easy to do when you accept it for what it is, a young and enthusiastic place where they are rather keen on quality buildings. It has a human scale that is a hangover from it being a small market town as recently as the early 20th Century. And did you know that it has more miles of cycle lane per head of population than any other town in Britain? And proper cycle lanes, too, through parkland rather than painted in beside busy roads. Unfortunately, the OS map doesn't show them, so I ended up battling with traffic on the ring road to reach the eastern suburbs and

The most striking feature of the church is the 16th century brickwork of the aisle, and the clerestory springing into view behind. The aisle has a neat crow-stepped parapet, and above the five windows lighting the nave is a corbel table running under the parapet, above which are six cone-shaped pinnacles. A leaded spire rises from the tower, a bell under a little roof of its own jutting out from it.

The oldest things the village has are a few Roman tiles in these walls; they must have been handled by Saxons in a building long since gone. The two arcades and the wide chancel arch give distinction to the church, and there is a touch of humour bequeathed to us by the carver of a bridled head from which one of the arcades springs, a warning against slander. The pride of the church is the Jacobean pulpit. Its elaborate canopy has pinnacles and pendants, and the pulpit has carvings of many beautiful devices. On the chancel wall is a brass portrait of Jane Paschall, who was laid to rest here a few years before they set up the pulpit. She is a fine figure in Elizabethan dress. Two more ladies share the only other striking monument, Amy and Margaret Gwyn, sisters who died in the middle of the 18th century, their portraits being on a marble oval below a cherub.

Here the scholar poet Alexander Barclay came in 1546 as rector. In 1508 he translated Brant’s Ship of Fools into English verse, and then became a monk of Ely, where he translated a life of St George. Scholars owe a special debt of gratitude to Great Baddow, for here also was born Richard de Baddow, who in 1326 founded the Hall which became famous as Clare College at Cambridge.

Simon K -

I got the train to Chelmsford, arriving soon after 8am. I quite like Chelmsford, a thing it is easy to do when you accept it for what it is, a young and enthusiastic place where they are rather keen on quality buildings. It has a human scale that is a hangover from it being a small market town as recently as the early 20th Century. And did you know that it has more miles of cycle lane per head of population than any other town in Britain? And proper cycle lanes, too, through parkland rather than painted in beside busy roads. Unfortunately, the OS map doesn't show them, so I ended up battling with traffic on the ring road to reach the eastern suburbs and

Locked, no keyholder. Everybody moans that this one is locked without

a keyholder, so I hadn't expected anything different, especially as it

was still only about 8.30 in the morning. I suspect the architecture

is the best thing here anyway. From a distance you see the spire, a

replica of that on the cathedral a mile or so off, but coming closer

it is very different, a late medieval red brick rebuild of the

clerestory looking like a grand country house with a flint tower

attached. Incongruous but attractive. Although Great Baddow is a

typical Essex suburb with estates and tower blocks, the church is in

the old village centre with early 19th century agri-industrial

buildings and a Tudor pub. They were putting on a psychic night, I

noticed - the pub, not the church. Wishing it had been open (there's

nothing worse than the first church of the day being locked) I headed

on through suburbia to Sandon.