Two churches: St Mary masquerading as C18 but essentially re-built in the C19 and C20, retaining, however, much interest inside, and All Saints which was rebuilt in 1973 to a design by Laurence King and Partners and wouldn't normally be eligible for inclusion but since I visited it is.

ST MARY THE VIRGIN. Red brick W tower with diagonal buttresses of 1658-9. C18 clock turret on the top. Part of the N aisle wall evidently also 1658-9. The church itself 1832, but renovated 1889 and much altered and enlarged at the E end in 1932. The octagonal shape of the piers e.g. is 1932. - HOUR-GLASS. Four in one. C18, from the Augustinian Church at Munich. - ALMSBOX. In the SE porch. Dated 1626. Small and with a pretty figure of a lame man. - PLATE. Cup of 1775; fine set of 1794. - MONUMENTS. Ursula Gasper, d. 1493, small brass (N arcade W end). - Sir Michael Hicks d. 1612 and wife, two semi-reclining effigies, propped up on their elbows, lying in opposite directions. The monument is probably not in its original state. - Sir William Hicks d. 1680 and his son Sir William d. 1703, large standing wall monument with standing figures of man and woman and between them semi-reclining, the father. Ascribed by Mrs Esdaile to B. Adey. - Newdigate Owsley d. 1714 small tablet signed by S. Tufnell. - John Story by J. Hickey 1787. Good standing figure of Fame against large grey obelisk. - Hillesdon children 1807 by John Flaxman. Monument with allegory of woman seated on the ground and reading. - William Bosanquet d. 1813. With fine scene of the Good Samaritan in relief. Also by Flaxman. - E. Brewster d. 1898. Still with the mourning allegorical female bent over an urn, just like a hundred years before. Signed by Gaffin of Regent Street, a firm which also goes back a long way. - In the Churchyard MONUMENT to Samuel Bosanquet, 1806 by Sir John Soane, of typically Soanian Neo-Greek detail. W of the church tower.

ALL SAINTS, Capworth Street. The church of 1865 by Wigginton. Behind it the SCHOOL with additions of 1909 by Frere, of a very delicate and original style.

LEYTON. Here came into the world the best-known boy of the Great War, and here went out into the world the best-known man of Africa. Leyton and its companion Leytonstone have memories of many great folk, but supreme among them are the immortal figures of Jack Cornwell and David Livingstone. In this maze of homes between Epping Forest and the River Lea one lowly house stands out in Clyde Place, Capworth Street, for here was born the boy who won the VC at the Battle of Jutland. We come upon Jack Cornwell at Little Ilford, where he went to school and where he now lies, but it was here that he was born, and the children of Leyton have put a tablet to their hero in the church of All Saints, close to his birthplace.

The church is a storehouse of Old Leyton, with many names of folk famous before Jack Cornwell, and with views and manuscripts and portraits framed in the galleries. It was rebuilt last century except for the tower, which comes from Cromwell’s time and has under its domed cupola a bell 600 years old. There is nothing older here, but brasses show us Ursula Gasper of 1483 and the Jacobean family of Tobias Wood, his wife, and their 12 children, with a punning verse about woods and trees. Five members of the Hicks family appear as lifesize figures under the tower, Sir Michael, secretary to Queen Elizabeth’s Lord Burghley, lying in his armour with his wife under a double canopy, their heads on their hands, while Sir William, who died in 1688, lies on another tomb with one of his sons beside his wife. Sir Michael has an epitaph which suggests that he wrote it himself, looking back on his happy life as a courtier:

Those things I desired in Iife I attained; pledges lately deemed the sweetest, a dear wife and a fortune. I was happy in my family; two sons and a daughter call me father. I began to long for Christ, therefore I willingly yield to death; willingly I leave wife, fortune, sons, and daughter.

There is an interesting group of memorials, some by Flaxman. On Sir Robert Beachcroft’s stone of 1721 is carved his lord mayor’s fur cape, sword, and mace; an 18th century merchant has an angel with folded wings as a tribute to his memory. There is a tablet to William Bowyer, one of 20 printers permitted to follow their trade in Charles Stuart’s England, and the print of a lost monument shows Sir William Ryder, the haberdasher who introduced woollen stockings into England from Italy about the time Raleigh was bringing tobacco from America. Another print shows Samuel Kempe, a Leyton vicar, who is wearing the soldier’s buff coat he wore when he preached in Cromwell’s time, having first placed his pistol on the cushion in front of him, beside the Bible. There is a Flaxman sculpture of a girl reading a book in memory of John Hillerson, and a wall-tablet also believed to be Flaxman’s, with the Good Samaritan. Other odd treasures here are a 17th century poor-box with a carving of a lame man, an hourglass brought from Munich in 1693, an old beadle’s staff, an ancient map by John Speed, some illuminated and jewelled parchments, and a fragment of a brass discovered in a kitchen.

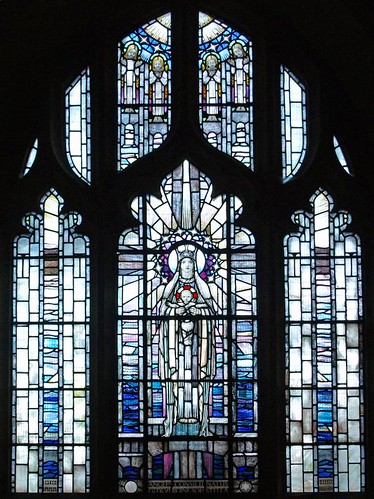

There is a little medieval glass in a small window in the south-west porch, a beautiful window under the west gallery given by the Girl Guides, and four fine heraldic windows, the one nearest the east having below it a parchment with the autograph of the King of Greece, who was here when the window was unveiled at a Masonic service. Poets and artists have combined to make two beautiful modern windows, inspired by Matthew Arnold and G. K. Chesterton. One is of the Good Shepherd, with a goat in his arms and these lines from Matthew Arnold:

He saves the sheep, the goats He doth not save.

So rang Tertullian’s sentence,

And on his shoulders not a lamb, a kid.

The other window of a blue Madonna with the Child in her arms is inspired by these lines of Chesterton:

The Christ Child lay on Mary’s lap

His hair was like a light.

In the churchyard lie a soldier and a vicar with astonishing records of service. The soldier was William O’Brian who served 60 years in the Army when it was not much older than he was. He died in 1733 and four years later died old John Strype aged 94, having been vicar here for 68 years, during which time he became famous as an antiquarian, wrote lives of Cranmer and other archbishops, and gave Leyton its church house, with a handsome doorway; he lived in it himself. John Strype’s father came to London as a refugee, and John was born at Houndsditch, went to St Paul’s School and on to Cambridge, and grew up to divide his time between preaching and writing, becoming vicar of Leyton in 1669 and remaining here till he died in 1737. All the time he was writing history and biography in his own rough way, accumulating a remarkable mass of curious information. His works were reprinted in 19 volumes early last century, but are now of little value. Dying at 94, he outlived his wife and all his children and much lamented that he left so much work undone. He wrote his own Latin epitaph, which has been inscribed on a memorial brass in the chancel floor, and there is a marble engraved with his coat-of-arms which has been remarkably preserved and is now under glass.

Here also lies Sir John Strange, who began life as a solicitor’s clerk, and used to carry his master’s bag to Westminster, where he saw a judge take his seat as Master of the Rolls, little imagining that he would occupy the seat himself. He sat in Parliament, was one of those who inquired into the conduct of Sir Robert Walpole, took part in the impeachment of Lord Lovat, and was Master of the Rolls for three years before they laid him here in 1754.

Among all these interesting people there lies also in the churchyard Sir John Cotton, who went to sea at 15 and lived through the exciting years of Napoleon. In the days when Trinity House raised 1200 volunteers to safeguard the mouth of the Thames. Pitt was colonel and Cotton was lieutenant-colonel. He wrote a book which gives much information about our coast lights at that time, and was awarded a medal for bringing from the East a grass of remarkable fineness and strength. His son William, who lies at Leytonstone, was a director of the Bank of England, and is remembered as having invented the automatic weighing machine for sovereigns; in his day it could weigh 23 a minute, accurate to the ten-thousandth part of a grain. He was the first man to stop the practice of paying men’s wages by orders on a public house, and though not very rich was a great philanthropist and delighted in building churches.

Leyton, which has brought Leytonstone within its bounds, has had a delightful mace made for the new borough, modelled on one made for the House of Commons in the time of the Stuarts; it is 48 inches long. In the Central Library is a tablet in memory of the Old Boys of Leyton’s schools who fell in the war; it was presented by the teachers of all the schools of the town, and each week a page of the Book of Remembrance is turned over so that the records of all the schools come round in their turn. At a library in Fairlop Road is a bronze plate recording the fact that John Drinkwater was born here. He must have loved these forest scenes in his boyhood, as William Morris used to do, for he, too, was an Essex lad, born at Walthamstow.

Leytonstone has a Roman milestone still standing, and its name comes from it; it gives the distance from London to Epping. There are several 19th century churches, St Andrew’s built by Sir Arthur Blomfield, and St John’s built largely through the enthusiasm of William Cotton, the bank director who lies in it. It is a white brick structure with stone dressings, a pinnacled tower, and a graceful spire. Its first vicar was a friend of David Livingstone, who came to stay with him on the eve of his journey to Africa. Here he received his last Communion from his friend before sailing for the Dark Continent on a mission which was to bring light to a thousand dark places and to him everlasting fame.