ST MARY MAGDALEN. Low C14 W tower with angle buttresses and tall timber spire. Nave and chancel without structural division, and S aisle with separate pitched roof. The nave is Norman, as witnessed by one small window on the N side. The rest C14-C15. N doorway with head corbels and angels in the spandrels; N porch of heavy timber. Inside, the arcade to the S aisle has octagonal piers and double-chamfered arches. There is also an early C16 S chancel chapel, separated from the chancel by a two-bay arcade with a composite pier and hollow-chamfered arches. - REREDOS with Corinthian pilasters and a broad segmental pediment, now at the W end, and COMMUNION RAIL, late C18, Metropolitan-looking and indeed said to come from a City church. - BENCHES, in S aisle, C15. - CHEST. Dug-out type, bound with iron, C12-C13. - MONUMENT. James Fishpoole d. 1767, graceful tablet of various marbles, with obelisk and urn.

GREAT BURSTEAD. Through the Romans, Saxons, and Normans its history brings us to a dramatic event of our own time. In this lovely hill country ancient Britons were at home before the Romans came; their earthenware has been found in a burial ground, with the coin of a British king and coins of three great Caesars: Trajan, Hadrian, and Constantine.

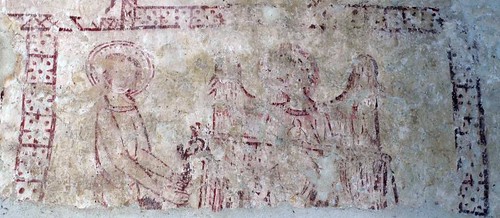

In this place of ancient memory lies a Saxon king, the 7th century Sebert; he lies in the great churchyard, in which an ancient yew is flourishing. The bold tower is 600 years old and has a shingle spire springing from the parapet. The Normans built the nave and one of their windows remain. There are two medieval porches, both with fine timber roofs and one timber-framed with a carved barge-board. In this porch are the stone heads of a king and queen and a carving of Gabriel bringing the good news to the Madonna.

The font, the roofs, the doors with their ironwork, one of the bells, and a little of the glass, have all come down to us from the hands of medieval craftsmen, and their work is also on a splendid array of oak pews.

Older than all these possessions is the huge dug-out chest with seven iron hinges, in which they kept the village documents guarded by three padlocks. It is possible that there were kept in this trunk the wages of the men who transformed the simple Norman church into the place we see.

There is a lovely oak reredos, and over the tablet of the Commandments is a golden-winged cherub so superbly wrought that it is believed to have come from the workshop of Grinling Gibbons. In the sanctuary are two carved Jacobean chairs.

Two events that come into our history belong to Great Burstead, one to the chancel of this church and one to the village itself. In the chancel one winter’s morning in 1607 stood a little wedding group. Christopher Martin was marrying Marie Prower, looking forward to great happiness in this Essex countryside. But, alas, the spacious days of Queen Elizabeth were gone, and the tyranny of the Stuart days had come, and they were to sail away in the Mayflower in search of freedom to worship God. Christopher was the treasurer of the ship, one of the inspirations of that immortal company of voyagers, and it is sad to have to record that within a month or two after reaching the new-found world of liberty they and their servant died from the hardships they endured. Their names are in the register here, and a few pages before is the name of Elizabeth Watts, a widow. Her husband was one of the heroes of the village, and one of the victims of the cruel reign of Mary Tudor.

The event of our own time which will not soon be forgotten was the coming down of a Zeppelin in the Great War. The Zeppelin was the L32, one of 12 raiders which came over Essex in the reign of terror of the autumn of 1916. Two reached London, killing 29 and injuring 99, but one never arrived and never returned home. Two airmen attacked the L32 and crowds of excited people saw the running fight. Soon a glow like that at the end of a cigar appeared at the end of the Zeppelin and suddenly the great airship was enveloped in flames. It came down burning from a height of 8000 feet, the second Zeppelin brought down in England, and in this church-yard where lies a Saxon king lie the men who perished with her.

Long before the Age of Zeppelins was the age of torture by fire in Smithfield and one of the bravest of 72 Essex victims of Queen Mary's persecution was Thomas Watts of Burstead. He was a prosperous draper here, a student of the Bible and a preacher. Married and with six children, and knowing the danger he was in, he sold all the cloth in his shop and gave his possessions to his family and much to the poor.

One day in the summer of 1555 he was brought before Bishop Bonner, and after three examinations was condemned to death and sent to Newgate. In June he was taken to Chelmsford and lodged in an inn with four other Essex men waiting to be burned. It is recorded that they had supper together and then joined in prayer, and that afterwards Thomas Watts prayed alone and left them to say farewell to his wife and his six children. “Let not the murdering of God’s saints cause you to relent,” he said to them; “I doubt not He will be a merciful Father unto you.” Two of his boys, not bearing to leave their brave father, pleaded with him that they might be burned with him, but they were led sorrowfully away. For 44 years his widow lived at Burstead, and when they laid her to rest, in a grave by the yew tree still growing near the porch, the rector sat down and wrote in his register these words:

Elizabeth Watts, widow of Thomas Watts, the blessed martyr of God, who for witnessing suffered the martyrdom in the fire at Chelmsford in the reign of Queen Mary, was buried this 10th day of July 1599, having lived a widow after his death and made a good end like a good Christian woman in God.

No comments:

Post a Comment