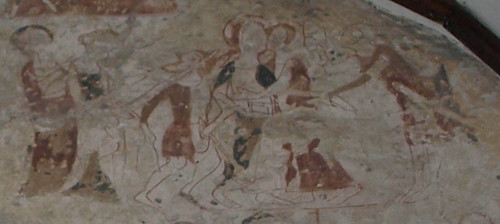

ST MARY. Nave, chancel, and W tower with shingled. broach spire. The nave is Norman, with Roman brick quoins and small original windows, one in the N, one in the S wall, also the remains of a S doorway - all with Roman brick dressings. Norman also the plain, broad chancel arch. The tower was added in the C13, also with much use of Roman brick. Lancet windows and W doorway with one renewed order of E.E. columns. Of the C13, but later, is the chancel, with restored lancet windows. The group of three at the E end is unusual in that they are stepped not only at the top but also at the foot. Sedilia and Piscina are original, but not specially ornate. C15 N porch of timber. - REREDOS. Of stone, fragmentary, at the NE end of the nave. What remains is part of the ribbed soffit of c. 1500. - BENCHES. Fourteen in the nave, straight-topped ends with linenfold decoration. - CHEST. Dug-out, heavily iron-bound, C13 or C14, in the nave. - PAINTINGS. The most valuable thing in the church is its wall-paintings above the chancel arch. They date from c. 1275 and were restored in 1936 by the late Professor Tristram. There are four tiers rising in size as the eye moves upwards. The lowest tier has small scenes, in the second one recognizes the Crowning with Thorns, the Mocking, the Scourging, Christ before Pilate, and the Carrying of the Cross. Above this the Last Supper and the Betrayal, and in the top tier the Entry into Jerusalem. The artistic quality is not high.

FAIRSTEAD. Few villages in the county are more remote; we come to it by a winding lane from lovely Terling. It has a shingled spire of the last years of Queen Elizabeth, set on a tower of 1200, pointing to the sky in the midst of limes, sycamores, and chestnuts. The capitals at its doorway have weathered the storms of over 700 years. But far older is some of the material in these walls, for there are Roman bricks halfway along the chancel showing where the Norman building ended and where our first English builders continued in the 13th century. The chancel arch has Roman bricks at the top, and in doorway, window, and wall these red bricks abound, mingled with pebbles and flints; it is as if the eager builders had said that any rough assortment would do, only let there be a church.

At least 700 years ago the wall over the Roman bricks in the chancel arch was made a picture gallery, and it is interesting to see that instead of painting the conventional Last Judgment the artists crowded several scenes in rows into their space. Next to the roof are Our Lord riding on the Ass; below are the Last Supper and the Betrayal (with Peter cutting off the ear of Malchus); in the third tier are Christ crowned with thorns, mocked, scourged, and brought before Pilate, while on the extreme right He is carrying His Cross. In a fourth row only two figures are at all clear. There are traces of later paintings on other walls and six red consecration crosses. There is a chest 700 years old, a dug-out nine feet long with two lids, 15th century benches in the nave, and in the belfry a bell which has been ringing for 600 years.

Four centuries ago a traveller would have seen a quaint figure roaming about these lanes. He was Thomas Tusser, the author who had come to test some of the 500 points of good husbandry of which he wrote. His theories met with very little practical success, and he confessed that Jack and Jill tithed so ill that he felt too heavily the burden of the daily pays and the miry ways. So Thomas returned to London, to die in a debtor’s prison, a stone of Sisyphus which could gather no moss, as Fuller said, or, as the epigram says:

Tusser, they tell me when thou wert alive

Thou, teaching thrift, thyself couldst never thrive;

So, like the whetstone, many men are wont

To sharpen others when themselves are blunt.

Flickr set.

At least 700 years ago the wall over the Roman bricks in the chancel arch was made a picture gallery, and it is interesting to see that instead of painting the conventional Last Judgment the artists crowded several scenes in rows into their space. Next to the roof are Our Lord riding on the Ass; below are the Last Supper and the Betrayal (with Peter cutting off the ear of Malchus); in the third tier are Christ crowned with thorns, mocked, scourged, and brought before Pilate, while on the extreme right He is carrying His Cross. In a fourth row only two figures are at all clear. There are traces of later paintings on other walls and six red consecration crosses. There is a chest 700 years old, a dug-out nine feet long with two lids, 15th century benches in the nave, and in the belfry a bell which has been ringing for 600 years.

Four centuries ago a traveller would have seen a quaint figure roaming about these lanes. He was Thomas Tusser, the author who had come to test some of the 500 points of good husbandry of which he wrote. His theories met with very little practical success, and he confessed that Jack and Jill tithed so ill that he felt too heavily the burden of the daily pays and the miry ways. So Thomas returned to London, to die in a debtor’s prison, a stone of Sisyphus which could gather no moss, as Fuller said, or, as the epigram says:

Tusser, they tell me when thou wert alive

Thou, teaching thrift, thyself couldst never thrive;

So, like the whetstone, many men are wont

To sharpen others when themselves are blunt.

Flickr set.

No comments:

Post a Comment