As far as I remember I was running late and briefly stopped at All Saints which was open but undistinguished so I just took a couple of quick exteriors and dashed off. This may have been ill-judged since a quick Google search shows some interest:

The nave of the church is 14th century or earlier; the chancel is 13th century or earlier; the tower and transept date from the 1840 improvements. At the back of the nave is an early 19th century font. Notice the carved heads around the base of the bowl. The original ancient font, was given to Wakes Colne church by a former vicar, Revd. Thomas Henderson, who was also rector of that parish.

The Nave is undistinguished except for the roof, which is its most striking feature. The nave dates from the 14th century, or possibly earlier. The tracery in each of the windows is different. The roof can be dated to 1360 by the carved heraldry held by the angels bearing the arms of the Baynard family. Notice also the carved roses at the apex of the main trusses. The 2 hammer beams at the chancel arch have lost their angel heads probably during the Reformation, or during the English Civil War. The 2 most western roof bays belong to the 1840 restoration.

The large window near the pulpit replaces the 1840 North transept, badly damaged and subsequently demolished after the 1884 Colchester earthquake. Near this window are the remains of a monument, sadly lost in the early 19th century. It was described in “A Gentleman’s History of Essex” 1772, as being of an armed knight, cross-legged, made of wood and reclining under an arch in the north wall. Tradition reports that he was the founder of this church and believed to be called Sir William de Messing. In an Essex guide book published in 1845, “Suckling Papers,” is this amusing comment: “My sole object in visiting this church was to draw this ancient monument, and my regret may easily be conceived, on learning that the late vicar had given it a short time before to the parish clerk, to be burnt as a piece of useless lumber…. The parish clerk has obeyed the directions of his tasteless superior to the very letter; not a fragment of this monument remains.”

Suckling also writes: “On the chancel floor lies a small effigy of a female… I have made a drawing of it lest parochial iconoclasm should consign it to the fate of the templar.” Fortunately, this did not happen!

The Royal Arms. This fine work is dated 1634 and almost uniquely bears the arms of the Prince of Wales on the reverse. Also can be seen the arms of the then Patron and donor, Hanameel Chibborne. It was presented at the time of absolute government by Charles I. The arms mark Chibborne’s loyalty to the King as well as commemorating his entering upon his inheritance, which was in the King’s hands during his minority. It could also mark Chibborne’s marriage to Mary Newton of Canterbury, on Christmas Day 1634 in this church. Notice the text, on the back; “Give thy judgements to the King O Lord: Thy righteousness to the King’s sonn”. The royal arms may originally have hung in the chancel arch: notice the 2 holes in the wooden hammer-beam arch next to the chancel arch.

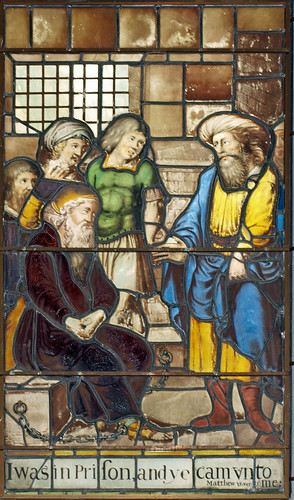

The East Window. This beautiful window represents the Acts of Mercy: St Matthew 25:35,36, and in the top part – Faith, Hope and Charity. The window was probably placed here by Sir Charles Chibborne who died 1619. It is believed that it may originally have been at New Hall, Boreham.

Notice particularly the delightful details of the distant landscapes, the window and brick details of the buildings and the bold use of the colours red, blue, yellow. Do not miss the four-poster bed in the lower light! During the English Civil War and the siege of Colchester, 1648, the window was carefully removed and hidden in the great chest, together with other church treasures, and hidden in the church’s vault, thus preserving it from destruction.

After the destruction of much stained glass in the reformation reign of Edward VI religious stained glass became acceptable once more, especially during the early years of the 17th century. By far the most significant of the glass painters at this time were 2 Flemish brothers – Abraham and Bernard Van Linge. Our window is by the famous Abraham.

Horace Walpole, the famous 18th century antiquarian, collected ancient stained glass. In 1749 he made a special visit to Messing to see this window, and described it as “an extreme fine window of painted glass”.

I think a re-visit is on the cards allowing more time for a proper appraisal!

I've re-visited and it was indeed worthwhile the chancel window alone being worth it.

ALL SAINTS. Mostly 1840, i.e. the W tower of red brick, not at all Essex in style, and the long S transept. Medieval are part of the nave and most of the chancel. In the chancel is what makes the church worth a visit, the PANELLING and CHANCEL STALLS of c. 1634 (date on the Royal Arms in the S transept). No classical features yet, the stall fronts with rusticated oval frames, the backs with rusticated blank arches separated by Corinthian pilasters. The ornament entirely Jacobean, but hardly any strapwork. - STAINED GLASS. In the E window, contemporary with the panelling and attributed to van Linge (Abraham who worked at Peterhouse, Cambridge rather than Bernhard). The Works of Mercy and figures of Faith, Hope and Charity. - CHEST. Iron-bound probably C13. - PLATE. Whole set of 1634, given by Captain Chibborne whose arms also appear on the reverse side of the carved Royal Arms. - BRASS to a Lady, c. 1540 (chancel).

I've re-visited and it was indeed worthwhile the chancel window alone being worth it.

ALL SAINTS. Mostly 1840, i.e. the W tower of red brick, not at all Essex in style, and the long S transept. Medieval are part of the nave and most of the chancel. In the chancel is what makes the church worth a visit, the PANELLING and CHANCEL STALLS of c. 1634 (date on the Royal Arms in the S transept). No classical features yet, the stall fronts with rusticated oval frames, the backs with rusticated blank arches separated by Corinthian pilasters. The ornament entirely Jacobean, but hardly any strapwork. - STAINED GLASS. In the E window, contemporary with the panelling and attributed to van Linge (Abraham who worked at Peterhouse, Cambridge rather than Bernhard). The Works of Mercy and figures of Faith, Hope and Charity. - CHEST. Iron-bound probably C13. - PLATE. Whole set of 1634, given by Captain Chibborne whose arms also appear on the reverse side of the carved Royal Arms. - BRASS to a Lady, c. 1540 (chancel).

MESSING. There are fragments of the Roman Empire in its church walls, and in its cottages huge beams that have supported their roofs four or five hundred years. Its church is one of the few that were enriched in the brief revival of church building in the early days of Charles Stuart. It happened that its vicar was a friend of Archbishop Laud, and in his day many things of beauty were added to the chancel. The vicar was Nehemiah Rogers, a fervent Royalist and "man of good note," as Laud said; he wrote on the parables, and one of his books commands a good price today.

He was also rector of Great Tey and Doddinghurst, where he lies. Round the walls is elaborate oak panelling divided by pilasters, with little cherubs peeping out above, and there are fine stalls for the choir. Swinging from a beam in a chapel is a gabled panel with the Royal arms of 1634 and Charles Stuart’s Prince of Wales feathers in faint colours on the back. There is an altar table of the same period, and in the tracery of the east window, with 14th century stonework, is 17th century glass by Van Linge, who knew so well how to paint the costumes of his age in vivid yellows, blues, and reds. In the upper lights are figures of Faith, Hope, and Charity, and six scenes below showing six kindly works of charity. This fine window was new when the fury of the Civil War burst over Essex, and we owe its existence today to the fact that it was taken out and buried. In the roof are 15th century angels, and there is a long ironbound chest in which the village documents have been kept for 600 years and are still kept today.

Simon K -

At first sight, this is rather an ugly church, a red brick tower dressed with freestone, as if in imitation of St Benet Pauls Wharf in the City, and beyond it a large Victorian nave, a result of earthquake damage and a rich and enthusiastic patron.

But the chancel and south transept are enough to propel the church into my Essex top 40. It is one of the best surviving examples of a Laudian worship space, all the fixtures, fittings and windows dating from 1637.

The glass depicts the Works of Mercy, a vast and exceptionally rare scheme for its date, and there are lovely Jacobean stalls, not choir stalls but communion stalls, where Laud imagined people would kneel to take the sacrament. There is a fabulous carved royal arms with the Prince of Wales feathers behind it, and the inlaid stone floor has an inscription from the new King James Bible.

It is a fascinating insight into a model of the Church of England

that lasted barely ten years before Cromwell and his henchmen

extinguished it.

Good job you did re-visit. I went today and it was firmly locked. Judging by the hole in a window on the south side I think I know why...

ReplyDeleteSenseless vandalism is just mind boggling and...senseless.

DeleteDefinitely senseless because it has caused this church to go into retreat.

ReplyDelete