Great Tey is an attractive village with an elevated situation, allowing the sturdy tower of its noble church to be seen for some distance, particularly from the south. This interesting church stands in an extensive and cared-for churchyard and certainly dominates the houses clustered around it. It is a magnificent tribute to the craftsmen of the 12th and 14th centuries and is a bold and silent witness to the faith which has been proclaimed within its walls for over eight centuries.

The earliest part of this building (which is but a fragment of its former glory) is the Norman Tower, which was erected about 1160 as the central tower of a cruciform church. It is not known who had it built, but possible names have been suggested, including Richard de Lucy and Baron Eudo (whose name is also associated with the building of Colchester castle). The Norman builders incorporated many Roman bricks and tiles in the masonry of this tower. West of it once stretched a long Norman nave and aisles, with Norman arcades.

The chancel was rebuilt during the early part of the 14th century, when the present transepts and probably also the aisles of the nave took their shape.

The church was a large and magnificent building when complete and it was not until the early years of the 19th century that serious trouble was discovered. The building was inspected by Wm. Tite and James Baedel (architects), who reported that the whole church, except the chancel, was dilapidated. Lead from the south aisle roof had been taken and used for bullets during the Civil War and grave danger was being caused by the northwest pier of the tower. This contained the spiral staircase and had weakened, transferring the weight of the tower to the north nave arcade and pushing the columns on the north side of the church some 5½ inches out of perpendicular. It was calculated that the cost of restoration would be £700 and the response of the church folk to this must have been the most embarrassing and regrettable mistake of their history. They decided that the price was too great and that the nave should be demolished and replaced by the present western annexe, designed by James Baedel of Witham. This was done in the year 1829 and the bill for the work came to £1,400 – exactly double the price of the proposed restoration.

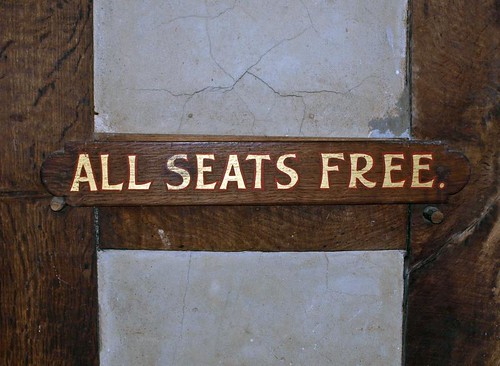

More restoration work was proposed in 1896 when James Brooks (who designed several famous London churches) drew up plans for re-seating the church and removing the western gallery. These were not entirely carried out, but in 1897 the tower was further strengthened and the bells re-hung; 25 cartloads of crumbling mortar, broken stones and bricks were taken from the tower and replaced by 8000 bricks and six tons of Portland cement. The chancel was restored in 1902, when many of the present furnishings were inserted.

Despite its chequered history, a tremendous amount of beauty and antiquity can still be seen both outside and inside the church.

It is worth standing back and viewing this church as a whole, and imagining its great nave stretching westwards of the fortress-like tower, which is 18 feet square and is one of the finest of its period. It is unbuttressed and has corner-quoins of stone and Roman brick. The brick, which is many years older than the tower, can also be seen framing the six recesses above the north and south transepts and the large single windows in the stage above. Flint and stone rubble appears in the masonry, also known as brown ironstone. This mixture of building materials gives the tower a variety of mellow colours. The belfry stage has large double Norman windows, with stone colonnettes, flanked by single openings. The embattled parapet is a later edition. The circular staircase turret in the northwest corner is also embattled, and is crowned with a distinctive weather vane, dated 1793. Beneath the arch of the eastern belfry window is a large carved stone head.

The early 14th century chancel is a fine example of Decorated architecture. It is strengthened by buttresses and has three double windows on the north and south sides, which have beautiful tracery and hood-moulds resting upon corbel heads. The priest’s doorway on the south side is noteworthy. Its hood-mould is carved with fleurons (flowers), foliage and ball-flower ornament and rests upon worn corbel heads. The superb five-light east window completes this chancel, and is flanked by interesting corbels. One appears to be a climbing monkey and the other a strange creature, thought by some to be a crocodile.

The north transept has a fine three-light mid 14th century window, with distinctive and very beautiful tracery. Its counterpart in the south transept matches the chancel windows and the east window of this transept is in the perpendicular style of the late 14th century. Carved into the south face of the south transept‘s eastern buttress, about 2 - 3 feet from the ground, is a mediaeval Mass dial.

The western annexe, of 1829, although a poor substitute for the former nave is, with its flanking porches, not unattractive and the four triple west windows are quite distinctive.

You enter the church by the south vestibule porch, on the north side of which can be seen the capitals of the first Norman arch of the nave arcade. These have been filled with a 15th century arch, which may have been an early attempt to counteract the weight of the tower. Above the inner entrance arch are the framed Royal Arms of Charles II.

The south transept is an attractive side chapel, with a trefoil-headed piscina in its south wall, showing that there was an altar here in the 14th century. The two windows in this chapel contain some interesting stained glass. In the tracery of the south window are four lions in the roundels and in the centre light of the east window is a human figure (maybe an apostle), in Continental Glass. These are the only fragments of ancient glass in the church. Nearby is the early 15th century octagonal font. In the stem are differing two-light traceried panels and the bowl, which has fleurons on its underside, has blank shields on its panels and some mutilated stone heads protruding at the comers. Its attractive oak cover, in memory of a churchwarden who died in 1975, is a simple but pleasing contribution of craftsmanship of our own times.

The tower is supported by simple Norman arches to the east and west, whilst those on the north and south are 14th century pointed arches, the capitals of the northern arch being more richly carved and decorated with fleurons.

The western gallery, which is built over the vestry, has an iron set of Royal Arms, dating from 1829. On the north side of the gallery is a handsome clock, which was presented to the church by the Rector in 1830. Square stones set in the wall beneath show the names of the Rector and Churchwardens at the time of re-modelling. To the south of the vestry entrance stands an unusual painted chest on wheels. This is unique in Essex and its original use is unsure. Some consider it to be Flemish or Dutch and made as a money or dower chest. Others reckon it to be German, and used for German troops. Some authorities date it from the 17th century, although one expert says that among the paintings on it are a man and woman in 16th century dress. Nearby, and now forming part of a seat near the main entrance, are three mediaeval bench-ends, of which the centre one has panelling on one side.

More interesting 15th century woodcarving can be seen in the priest's stall, where a further four bench-ends have been incorporated. The tops of these have small carvings, the most interesting of which can be seen in the eastern bench-end of the seat - showing a Scotsman in a kilt, and complete with bagpipes! He faces east.

The chancel is of noble and dignified proportions and the lovely window-tracery can be further appreciated from the inside. The 14th century moulded wall plates of the roof still survive at the tops of the walls.

In the south wall is a fine 14th century piscina, with an ogee-headed trefoil arch, flanked by mouchette and dagger carvings. The water in which the sacred vessels and the priest's hands were cleansed at the Eucharist was poured down the octofoil drain. The stone forming the back of the piscina recess has small incised crosses, which can only indicate that this slab once formed the mensa (or top stone) of a small altar in pre-Reformation times.

West of the piscina is the triple sedilia. These were seats for the Celebrant, Deacon and Sub-deacon at High Mass. Much of the stone canopy work is a very careful and worthy 19th century reconstruction. The simple arches at the rear are original however, as are also the semi-circular responds at the east and west ends.

Most of the furnishings of the church date from 1902, including the reredos. The altar is a 17th century Communion Table and of the same date is the chair on its north side. The pulpit is clearly earlier than the other furnishings and may well date from 1829, although some authorities believe it to be as early as the 17th century.

The memorials of the church are all of 19th and 20th century date and are not of great architectural interest. Several commemorate members of the Lay family, and the glass in the east window was inserted in 1861, in memory of J.W. Lay. On the north chancel wall is a small tablet to the Rev‘d J .B. Storry, who was parish priest here during the 1829 re-modelling, who gave the clock in the gallery and who was here for 43 years, until his death in 1855. His successor was Rector here for 38 years.

ST BARNABAS. In Norman times this must have been a magnificent church, and one would like to know the reasons for this display in this particular place. The crossing tower is one of the proudest pieces of Norman architecture in the county. The nave had aisles or at least one aisle, and there were no doubt a chancel and transepts. As it is, the chancel and transept have only C14 features and the nave was pulled down in 1829. The tower is of four stages with much Roman brick for dressings. The lowest stage must have communicated with the roofs. The second has on each side small coupled groups of three arches, the third two large windows, and the fourth the bell-openings with a colonnette and side windows. There is a circular stair turret higher than the tower. The battlements are later. Inside, the plain E and W arches are preserved. The C14 chancel is also a fine piece of work, with a very large five-light E window with flowing tracery, and two designs of Dec motifs in the tracery of the two-light N and S windows. The N transept N and S transept S windows are of the same date. So are the (much restored) Sedilia: three arches on shafts with nobbly foliage in the spandrels. The stump of a nave of 1829 is flanked by porches, and in the S porch one circular pier of the Norman nave is still recognizable with a low capital with angle volutes. - FONT. Octagonal, Perp, with shields in circles or quatrefoils. - PULPIT. Plain, C17, with decorated lozenge-shaped centres of the panels. - BENCH-ENDS. C15, with traceried panels and poppy-heads, used in the Reader’s Desk. - PLATE. Cup with band of ornament, and Paten, both of 1561 .

GREAT TEY. A huge Norman tower, 18 feet square and with many windows, proclaims to us from afar that we are drawing near a place which was a centre of busy life in ages past. This massive tower has Roman bricks in it, large and small; in the walls and in the arches of the windows we find these relics of Roman Britain, looking down on a great churchyard and towering above 16th and 17th century cottages.

In the neighbouring fields are farms with roofs and timbering of the 15th century, whose owners worshipped in the Norman church when splendid buildings clustered about the central tower. One pier remains of them all, buried in a modern wall; only the beautiful 14th century chancel and transept, indeed, remain to share the splendour of the tower, for the Norman nave and aisles were pulled down in our own time.

The outer walls of the chancel have beautiful tracery in the east window, and there is neat carving of heads and grotesques on many projecting stones, the most remarkable being a crocodile and a climbing monkey. The stones on which the gable rests are carved with grotesques and ballflowers, while a bishop and a bearded man look down on all who enter by the lovely priest’s doorway.

Two of the tower arches are Norman but the side arches have mouldings of the 14th century. Both the piscinas are of that time, one elaborately carved and the other backed by part of the Norman altar top with three consecration crosses on it. The font has been here 500 years and has heads on its bowl. On four 15th century poppyheads in a reading desk are a crowned head and a kilted man playing bagpipes. On a 17th century chest are paintings of a man and a woman. The fruit and flowers on some medieval woodwork has been copied in a modern window.